And so, we came to it again. An enthusiastic assertion somewhere on social media that it was somehow un-Indo-European to bow to one’s Gods, and much which is entailed with that.

I say “we came to it again”, because seriously – this seems to keep coming up, despite it being a very well attested fact that people seem to keep taking issue with here.

In this particular case, what had happened was a reasonably well-followed “European Pagan News” account on twitter had posted a quote, which read thus:

“Because he is not a ‘servant’ or ‘slave’ of a jealous and absolute God, the Indo-European generally does not pray on his knees or bent towards the earth, but standing with his gaze turned upwards, arms outstretched towards heaven.”

This was apparently a remark made by one “Hans F.K. Günther” circa 1934 in a work whose title appears to translate as “The Religious Attitudes of the Indo-Europeans” – and while I’d never heard of this Günther before, having just googled him I see he’s referred to in scholarly literature as having picked up the … odd epithet of “Race-Pope” (“Rassenpapst”) for his contributions to German academia through the 1930s.

Now, it has never been my habit to seek religious guidance upon matters Indo-European from a Pope – be they Italian, German, or even Argentinian. And having also taken a cursory perusal of the book in question’s opening chapters … well, let us just say that this has given me no reason to seek to change that stance.

But it is not our purpose to try and de-legitimate the quote via taking specific aim at its utterer. That would be a decidedly incorrect approach.

Why so?

Because he’s most certainly not the only guy to come out with something like this (the … non-bowing etc. advocacy, I mean) – and it does absolutely nothing to counter the position, the feeling, of those who do assert such.

After all, it absolutely does not require one to be a card-carrying member of the … certain political party in order to have bad theology & remarks upon religious praxis. Perhaps ironically, I’m sure that the rather … radical-egalitarian potential rendering for his sentiment within that quote [viz. not being a “‘servant’ or ‘slave'” of Gods, and therefore not bowing etc. as one might toward a lord, a king or a queen] would also find some resonancy amidst persons whose personal politics would prove to be emphatically the exact opposite of this Günther character’s ; and I suppose the modern Wiccan enthusiasm for insistently declaring that rather than “worship” Gods, they instead “work with” Them, in tones of organizing a car-pool to the office-job, might likewise fit in here somewhere, as well. But I digress.

As applies Günther’s assertion, it’s frankly bizarre. Because it’s prima facie totally incorrect. And with some pretty prominent exemplars which serve to handily demonstrate exactly that. It is to these which we shall now turn.

Xenophon, in his Anabasis, has perhaps one of the most famous. In rather … beleaguered circumstances, he found himself rather literally ‘rallying the troops’ (some ten thousand Greek soldiers) to fight a valiant breakout, straight through from the heart of the Persian Empire toward the hoped-for relative sanctuary of their fellow Hellenes’ settlements upon the Black Sea.

The relevant portion to Xenophon’s inspiring speech [III 2 13] reads, in the Dakyns translation, thusly:

“For you call no man master or lord ; you bow your heads to none save to the Gods alone.”

Brownson’s translation has it as:

“[…] for to no human creature do you pay homage as master, but to the Gods alone.”

You will note the “bow [their] heads […] to the Gods” / “pay homage as master”.

And, lest it be suspected that this is some mere translation artefact … here’s the line in the Ancient Greek.

What does it say?

“οὐδένα γὰρ ἄνθρωπον δεσπότην ἀλλὰ τοὺς θεοὺς προσκυνεῖτε.”

What does this mean?

Well, sure, to no man [anthropon – ἄνθρωπον] as master [Despoten – δεσπότην] … but the Gods [Theous – θεοὺς] they do bow to.

The word for bowing there is προσκυνεῖτε – proskyneite.

What does this mean?

The etymology is direct. Proskuneo [προσκυνέω] = Pros (as in movement (down) towards) + κυνέω, ‘kiss’ (which is, oddly enough, a cognate of same).

So yeah, face down and toward the God.

Now this might sound a bit abstract … but here’s the thing. Xenophon’s comment comes immediately following a QED for it.

To quote, again, from the translations [III 2 8-10], beginning with Dakyns:

“If, on the other hand, we purpose to take our good swords in our hands and to inflict punishment on them for what they have done, and from this time forward will be on terms of downright war with them, then, God helping, we have many a bright hope of safety.”

The words were scarcely spoken when some one sneezed, and with one impulse the soldiers bowed in worship ; and Xenophon proceeded : “I propose, sirs, since, even as we spoke of safety, an omen from Zeus the Saviour has appeared , we vow a vow to sacrifice to the Saviour thank-offerings for safe deliverance, wheresoever first we reach a friendly country ; and let us couple with that vow another of individual assent,’ that we will offer to the rest of the Gods according to our ability.’ “

And, per Brownson:

“[…] but if our intention is to rely upon our arms, and not only to inflict punishment upon them for their past deeds, but henceforth to wage implacable war with them, we have—the Gods willing—many fair hopes of deliverance.”

As he was saying this a man sneezed, and when the soldiers heard it, they all with one impulse made obeisance to the God; and Xenophon said, “I move, gentlemen, since at the moment when we were talking about deliverance an omen from Zeus the Saviour was revealed to us, that we make a vow to sacrifice to that god thank-offerings for deliverance as soon as we reach a friendly land; and that we add a further vow to make sacrifices, to the extent of our ability, to the other Gods also.”

He’d said “Soterias” [‘Deliverance’], and ten thousand hardened Greek soldiers all drop in reverence to the God [“προσεκύνησαν”] – Zeus Soter [The Savior].

Now, as applies the sneeze being a Divine Omen … it seems a bit of a mundane thing, I must confess – yet at the same time, how can you be sure that a sneeze is an omen and not just a sneeze?

When ten thousand soldiers drop to their knees … you can generally tell !

Also, sticking with the Hellenic end of things [somewhat] … this notion of ‘servant’ etc. – the term Xenophon had used, Despotes, is very much in attestance for Gods : here’s an example from Euripides’ The Bacchae viz. Dionysus.

“Χορός

ἰὼ ἰὼ δέσποτα δέσποτα,

μόλε νυν ἡμέτερον ἐς

θίασον, ὦ Βρόμιε Βρόμιε.”

[582-584]

Which, per the Buckley translation:

“Chorus:

Io! Io! Master, master! Come now to our company, Bromius.”

But we can, I think, do better:

Here’s Herodotus [IV 127] presenting the Scythian king Idanthyrsus in reply to the would-be world-emperor Darius:

“To this message Idanthyrsus, the Scythian king, replied: — “This is my way, Persian. I never fear men or fly from them. I have not done so in times past, nor do I now fly from thee. There is nothing new or strange in what I do ; I only follow my common mode of life in peaceful years. Now I will tell thee why I do not at once join battle with thee. We Scythians have neither towns nor cultivated lands, which might induce us, through fear of their being taken or ravaged, to be in any hurry to fight with you. If, however, you must needs come to blows with us speedily, look you now, there are our fathers’ tombs — ;’Seek them out, and attempt to meddle with them — then ye shall see whether or no we will fight with you. Till ye do this, be sure we shall not join battle, unless it pleases us. This is my answer to the challenge to fight. As for lords, I acknowledge only Jove my ancestor, and Vesta, the Scythian queen.”

[Rawlinson translation]

And, to zone in on the particular point of interest here – from the Godley translation:

“[…] as to masters, I acknowledge Zeus my forefather and Hestia queen of the Scythians only.”

[IV 127 4]

Which, in the Ancient Greek –

“[…] δεσπότας δὲ ἐμοὺς ἐγὼ Δία τε νομίζω τὸν ἐμὸν πρόγονον καὶ Ἱστίην τὴν Σκυθέων βασιλεῖαν μούνους εἶναι.”

Or, phrased more simply –

Idanthyrsus sees no issue hailing his (ancestral) Gods as Masters [ “δεσπότας” – ‘Despotas’ – and yeah, ‘Despotes’ shows up in Ancient Greek usage meaning ‘Master’ with an emphasis in the particular sense of ‘of Slaves / Servants’ , because ‘Household’,] … with this being pointedly (and by him / his scriptwriter, very much intentionally) contrasted with Darius’ claim to the same title, as Darius had re-iterated in the immediately preceding passage [IV 126] – referring to himself in relation to Idanthyrsus as “δεσπότῃ τῷ σῷ” : “Your Master”, as Godley’s translation puts it; “Thy Lord”, the Rawlinson.

Now, as for why I make a point of mentioning various of the above … it’s because I was rather pointedly bemused by this Günther character’s quip about how the Indo-European allegedly eschews bowing to Divinity “because he is not a ‘servant’ [of God(s)]” – but instead is supposedly “standing with his gaze turned upwards, arms outstretched towards heaven.”

In essence, Günther’s claim should appear to be that the Indo-European does not bow nor regard God(s) as Master(s) because he (or, for that matter, she) reveres Heaven.

Except hold the phone …

Who was that we just heard Idanthyrsus proclaim he would acknowledge as his ‘Despotes’?

Why, I do believe the word used was “Δία” [‘Dia’] …

… and in Xenophon, the God these Greeks have all literally just bowed in relation to – “Διὸς” [‘Dios’].

That being the Lord ‘Bright Sky’ – better known, to these contexts perhaps, as ‘Zeus’ (but with ‘Dia’ and ‘Dios’ also showing up to mean ‘Heavenly’ when utilized in various adjectival formats, etc.) … ref. Sanskrit ‘Dyaus’ (i.e. ‘Dyaus Pitar’ – Jupiter), where the ‘Heaven’ coterminity for its Lord is even further overt in our most immanent understanding. (A well-chosen construction, to be sure, Xenophon’s “οἰωνὸς τοῦ Διὸς τοῦ σωτῆρος ἐφάνη” – we are amused by the other meaning for “oionos” (in relation to ‘Raptor’; the more direct sense here is ‘omen’) , but more especially pleased via the pointed radiancy for “φαίνω” [‘phaino’] which (in)forms the basis for “ἐφάνη” [ephane], for ‘revelation’.)

Indeed, the “Hestia, Scythian Queen” / “Vesta, Queen of the Scythians” [as translated by Godley and Rawlinson, respectively] / “Ἱστίην τὴν Σκυθέων βασιλεῖαν” [for the Ancient Greek original] hailed via Idanthyrsus justly-proud declaration, as this is Scythian, is Tabiti – a Solar Goddess along the lines of our (Hindu) Aditi.

So, again, as with ‘Dios’ [viz. our Dyaus – Rudra] engaging with Sky as a powerful Master / Mistress indeed.

And while it can be fairly argued that Herodotus’ presentation of this exchange is just exactly that … a Greek making up dialogue for a dramatic encounter – it nevertheless is presented positively, valorously, and in-line with the Hellenic ideal viz. that which we observed presented via Xenophon to his comrades, from earlier.

It’s also if you check the next paragraph from the relevant section of Herodotus [IV 128], very much in direct contrast to the Scythians’ presented outrage at notions of slavery / having to acknowledge ‘masters’ amongst other men. [“οἱ δὲ Σκυθέων βασιλέες ἀκούσαντας τῆς δουλοσύνης τὸ οὔνομα ὀργῆς ἐπλήσθησαν”.]

So, again as with Xenophon – no contradiction.

Meanwhile, of course the Greeks do not have an Indo-European monopoly upon bowing in reverence to Gods.

Hindus also undertake Pranama – ‘Pra’, again, ‘forward’, and ‘Nama’ [from PIE *Nem / *Nem-² , the latter per Pokorny] as ‘bending’.

Within his ‘Etymological Dictionary of Latin’, de Vaan, as a tangent, makes this rather interesting observation with regard to ‘Nemus’, described by he as “wood, forest” (c.f., one presumes, the ‘Nemorensis’ for Diana of the Grove of Nemi … but more upon that some other time) and as rooted in PIE *nem-o/es- , which he observes to be “what is distributed, sacrifice”, this PIE origin also producing Sanskrit “námas- [n.] ‘worship, honour’,” (hence our most immediate interest for his work herein).

To quote him more directly (and at length):

“The meaning ‘forest, (holy) clearance’ is shared by Greek, Celtic and Italic. It originates from ‘sacrifice’ > ‘the place of the sacrifice’. In Ilr. [‘Indo-Iranian’], the -stem means ‘worship’.

LIV assumes two different roots, *nem-1 ‘to distribute’ and *nem-2 ‘to bend’, but the meanings are distributed complemeritarily across the IE languages:

Ilr. and Toch. have ‘to bend’, the European languages ‘to distribute’ or ‘to take’.

Since the s-stem is attested in all languages and presupposes the verbal meaning ‘distribute’, there can be little doubt that PIE had only one root *nem-.”

To phrase that more directly (if succinctly): effectively the ‘worship/reverence/offering’ angle and the ‘bowing’ angle appear heavily coterminous, viz. in what turns into Sanskrit ‘Namas-‘ etc.

That is to say – it’s something which should appear so familiar and endogenously archaic to the IE as to have, in de Vaan’s apparent view, the singular shared root (PIE *nem- ) informing both the terminology for ‘bowing in reverence’ as for ‘offering in reverence’.

This evidently would have been quite an ancient thing indeed for the ‘bend’ [‘bow’] sense to not be restricted to, say, Indo-Iranian – but also to show up in Tocharian, as well. This matters rather significantly, as despite their relative geographical propinquity it appears that Tocharian and Indo-Iranian branched off from the trunk of the (Proto-)Indo-European tree quite separately – and, as applies what would become Tocharian, by many accounts very early in the whole process indeed (second only to the splitting off of the Anatolian suite, upon the basis of various lexical etc. evidence).

I did pause to contemplate whether the co-occurrence for *nem for, as Adams’ Dictionary of Tocharian B puts it [viz. “näm-“], “bend (toward)”, “bend, bow (as a mark of respect)”, might perhaps have been one of those various assimilations more direct from Sanskrit (or, for that matter, the Iranic languages) at a relatively late(r) point within Tocharian’s existence … yet there is no suggestion that this was the case in any of the academic literature I’ve parsed upon the subject. Indeed, Adams’ aforementioned effort states quite directly that “AB [both Tocharian A & B] näm- reflect PTch [Proto-Tocharian] *näm- from PIE *nem- ‘bend, incline’” – as well as , to be sure , noting Beekes’ effort to “suggest a distinction between nem- ‘bend’ (in IndoIranian and Tocharian) and nem- ‘share out’ (in Greek, Germanic, and Baltic).” Which I mention in part because, if I am honest, having long observed with animosity Beekes’ apparent efforts at what I would almost term downright linguistic vandalism as applies asserting purported ‘non-Indo-European’ originations for a vast swathe of Ancient Greek mytho-religious terminology (regardless of what seemingly almost everyone else in the field regard as reasonable PIE etymologies and fairly decent broader IE – Sanskrit, etc. – cognates) … well, if he says something like this, then I find myself almost compelled to at the very least *initially* ‘interestedly consider’ the opposing point of view.

But let us move forward.

The Germanic / Nordic sphere is pretty much ‘Ground Zero’ for much of the modern objection-ism to notions of Bowing to Gods, Fearing Gods, and even (with (in)appropriate deference to everybody’s favourite black metal placenta cultists) Regarding Gods As Gods – let alone actually Worshipping Gods, it should seem.

This is NOT to say that all (or even most) persons operative within or otherwise connected to said sphere are like this. But with the bemusing exception of some relatively new grift-cults which have cropped up looking to cash in on the Classical IE heritages, it’s definitely where the most prominent concentrations for this kind of thing are to be found.

Now I am also not intending to get into the ‘whys’ for this recurrent correlation – suffice to say there’s a few things to do with both the sphere itself (being likely the largest and most ‘above-ground’ prominent means you attract all sorts, for a start …), and a few things to do with some of the people who wish to move within it (for instance: Christian upbringings being rebelled against leading to a downright allergic-reaction approach to anything which even vaguely reminds them of their parents’ religion; people who seem to have innate problems with ‘Authority’ or ‘not being the centre of attention / the universe’ and opposition to monarchy & aristocracy which then ‘scales up’ somehow to similar antagonism toward proper veneration for Gods upon exactly the same basis … seriously, I’ve seen it propounded ‘in the wild’.) .

A much more in-depth exploration for the whole thing can be found in Galina Krasskova’s rather well-written “To Bow or Not to Bow”; which I’m just going to proceed to quote verbatim from (with some slight alterations of formatting to more easily include the original-language materials being translated, as well as one of her footnotes), as applies the textual attestations for bowing to Gods being a thing in Germanic pre-Christian religion:

“Despite this conflict, if one examines the body of writing that Heathens term “lore,” there is ample evidence for precisely the type of embodied venerative practices so problematic to many mainstream Heathens today. Tacitus in the first century C.E. in his Germania, discusses the very physical reverence of the Germanic tribes about which he was writing:

“Reverence also in other ways is paid to the grove. No one enters it except bound with a chain, as an inferior acknowledging the might of the local divinity. If he chance (sic) to fall, it is not lawful for him to be lifted up, or to rise to his feet; he must crawl out along the ground.”

[Latin: XXIX “[3] est et alia luco reverentia: nemo nisi vinculo ligatus ingreditur, ut minor et potestatem numinis prae se ferens. si forte prolapsus est, attolli et insurgere haud licitum: per humum evolvuntur.”]

It is clear from Tacitus’ description that not only did the Germanic tribes accept ritual prostration, it was actually required under certain circumstances specifically as a demonstration of the person’s inferior position to the Deity in question. There is no ambiguity about the expected power dynamic nor the appropriate bodily response here.

The tenth century Arab traveler, Ibn Fadlan notes a similar practice of prostration during his sojourn among the Rus:

“The moment their boats reach this dock every one of them disembarks, carrying bread, meat, onions, milk and alcohol and goes to a tall piece of wood set up in the ground. This piece of wood has a face like the face of a man and is surrounded by small figurines behind which are long pieces of wood set up in the ground. When he reaches the large figure, he prostrates himself before it and says, “Lord, I have come from a distant land…”

[…]

Evidence in the Icelandic Sagas is even more extensive. Two examples will suffice.

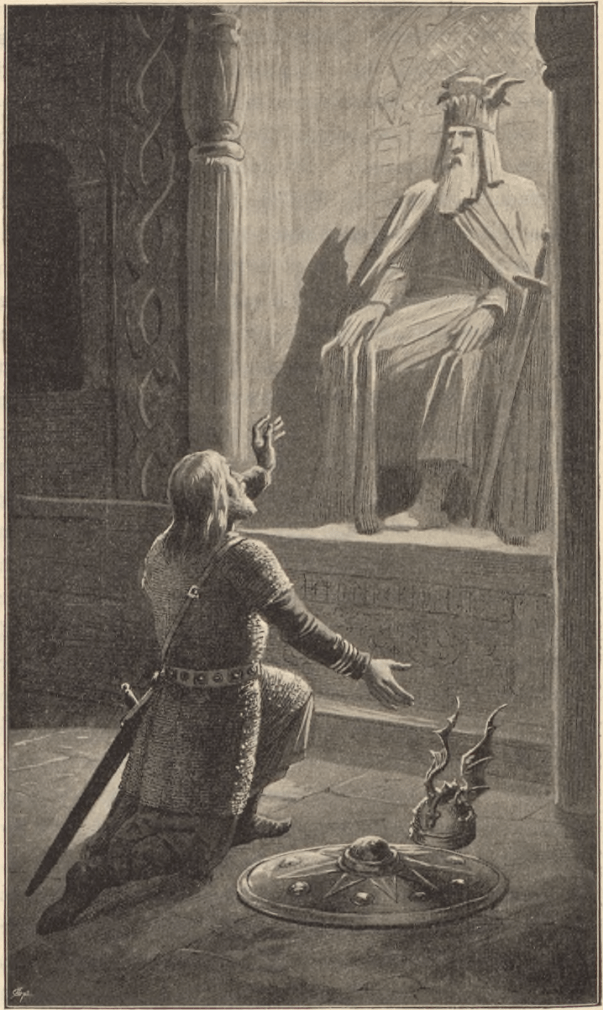

Firstly, Kjalnesinga Saga 3 gives the example of a man named Búi who is prosecuted by Þorsteinn, the son of a temple goði (priest) for his [improper] beliefs, specifically because Búi refused to prostrate himself before images of the Gods, as was customary.

Búi’s sentence is severe: full outlawry, however, he returns and murders Þorsteinn while the latter is lying face down in veneration in front of the statue of Thor in the temple.

In the second example, Harðar saga og Holmverja 38 gives the story of Þorsteinn who often goes to the blóthús (temple, place of sacrifice) where he kneels or prostrates himself in front of the sacred stone:

“When Þorsteinn came, he went into the temple and fell down before the stone at which he had made sacrifice and there he remained speaking before it.”

[In the original: “En er Þorsteinn kom, gekk hann inní blóthúsið og féll fram fyrir stein þann er hann blótaði og þar stóð í húsinu og mæltist þar fyrir.”]

This act is presented as unremarkable and normal. It was not presented in the Sagas as piety out of the ordinary. In fact, far from eschewing piety and physical veneration in holy places and before sacred images, the Sagas give numerous examples of precisely the type of reverence so contested in modern Heathenry. [footnote: Examples include Landnamabok 1.9, the Jomsvikinga Þattr, and part of the Norwegian Rune poem (the poem for Sol).]

This is significant given the authority these sources have for the average Heathen in directing the nature and course of ritual and personal worship. This evidence is largely ignored amongst contemporary Heathens who oppose prostration and kneeling, or who customarily interpret it in a way that suggests such reverence was not in fact the norm.”

Now, to (almost) finish with, I’d like to pick up upon one of those exemplars that Krasskova makes mention of – that being the ‘Sol’ portion of the Norwegian Rune Poem; which we’ll reproduce here in its original languages, as found in the ‘ᚱᚢᚿᛂᛦ seu Danica Literature Antiquissima’.

ᛋ. ᛂᚱ ᛚᛆᚿᚦᛆ ᛚᛁᚢᛘᛁ:

ᛚᚢᛐᛁ ᛂᚴ ᛆᚦ ᚼᛂᛚᚴᚢᛘ ᚦᚮ-

ᛘᛁ.

Sol er landa liomi:

Luti eg ad helgum

domi.

ᛋ. ᛂᚱ. Sol (hoc literæ nomen) lumen terræ.

Aſþiciunt oculis ſuperi mortalia juſtis.

ᛚᚢᛏᛁ. Sacra religiose tractanda.

Procul eſte profani.

Luti id eſt veneror, cernuus adoro, reverenter habeo.

Now, as applies that second passage of the three, the second line thereof reads:

“lúti ek helgum dóme”

Which, to go word-by-word [and somewhat ‘simplifying’ things by just using the Old Norse, for the purposes of this presentation]:

“bow [lúta] I [ek] to Holy [heilagr] Decree [dǿmi]”

The Latin handily clarifies ᛚᚢᛏᛁ / “Luti” to be “veneror, cernuus adoro, reverenter habeo”:

“venerate/worship [‘Veneror’], bowed forward [‘Cernuus’] supplication/adoration [‘Adoro’], have [‘Habeo’] awe/reverence [‘Reverenter’].”

Something one would appear to be doing in relation to the Heavens, once more, given it’s the Sun.

As brief points of interest – some of those Latin sentences in the third paragraph are actually drawn from prominent works of antiquity.

So, “Aſþiciunt oculis ſuperi mortalia juſtis” – “Adspiciunt oculis superi mortalia iustis!” within its original setting – can be found at XIII 70 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Which, in the More translation, is rendered as: “The Gods above behold / the affairs of men with justice.”

“Procul eſte profani”, meanwhile, should be rather well-known in its own rite – in the original Latin and context [Aeneid VI 258]: “Procul O procul este, profani […] totoque absistite luco” … which, as it should happen, is the shouted order of the Priestess of the place [the Sibyl – the ‘Vates’ of the “Conclamat Vates” in the middle there] imminently prior to the arrival of the Dread & Terrific Goddess, Hekate, in receipt of the sacrifice that is being conducted and which coincides with Aeneas beginning his katabatic journey to the Underworld.

What does it mean?

“‘Away! Away! You that are uninitiated!’ shrieks the Seer, ‘withdraw from all the grove!”

[Fairclough translation]

Now, as a further point of interest … that actual situation within the course of the Aeneid is taking place imminently prior to Dawn [“Ecce autem, primi sub lumina solis et ortus,” – VI 255]; and, as pointed out by Connington’s commentary thereupon, should seem fairly directly correlate (even overtly based upon) Hecate’s arrival in very similar circumstances (i.e. pre-Dawn, and for Her Sacrifice) when Called Upon by Jason in the course of the Argonautica [III, esp, 1211-1220].

So, a rather definite i) Solar and ii) Worshipful connexion there, then. One which does not necessarily require my own observation for Hekate as Solar Goddess (hence the situation for the Sun rising into the Sky as the effective transition accompanying Her Arrival within the context of these Rites aforementioned via Aeneas and Jason – ‘Underworld Sun’, most particularly salient, also !) in order for it to make sense. But we digress.

The point made herein with this textual exemplar is a simple enough one:

One does indeed Bow to the Divinity, the Solar Divinity, and said Solar ‘Decree’ – this being what a Ruler / Arbiter most supreme does, via very definition as to that fact (‘dóme’, akin to ‘Doom’, having just such a sense – viz. ‘Judgement’, as well … the ‘Doom Upon Ye’).

And whilst one occasionally (if rarely) encounters suppositions for this verse as having evinced a Christian saliency to proceedings … I think that we have adequately demonstrated that the effective charge of bowing to Gods and the Divine Rulership of the Worlds – those ‘Regin’ (‘Rulers’ – c.f. Voluspa 6 : “Þá gengu regin öll / á rökstóla, ” … and with particular noting of just what sorts of Seats those are … ) – is most certainly not some kind of Christian phenomenon foreign to the Indo-European religious world(s).

Quite the contrary, in fact.

Now there is one final point which I wish to make about this – and that concerns how all of this (assumedly) happened in the first place.

By which I mean the aforementioned circumstance of , as I had phrased it earlier:

“a reasonably well-followed “European Pagan News” account on twitter had posted a quote, which read thus:

“Because he is not a ‘servant’ or ‘slave’ of a jealous and absolute God, the Indo-European generally does not pray on his knees or bent towards the earth, but standing with his gaze turned upwards, arms outstretched towards heaven.””

They hadn’t posted the image which bore the maxim in question themselves – they’d retweeted it. Or quote-tweeted it, to be more specific, with a translation from French of the statement in question.

They also, to be fair and sure, quote-tweeted my (sub-)thread of replies pointing out the whole thing was massively incorrect, bearing the comment: “A really interesting and well-founded thread on the subject of bowing before deities in the Indo-European traditions 👇🏻” – so that was nice of them, and would appear to suggest that they’re i) open to changing their minds about things when presented with evidence, ii) not actually dyed-in-the-wool adherents to the sorts of viewpoint which that Günther chap was associated with. Which is also nice.

I suspect what had happened was they saw an image bearing said quote, which was sourced from a book entitled “La religiosité indo-européenne” … and therefore assumed that it was an accurate statement of, well, The Religion of the Indo-Europeans [as in, the actual religion(s) thereof] – rather than some guy’s very bemusing headcanon which is basically comprised of actively rejecting a whole lot of the actual evidence in favour of Things He Wanted To Believe To Be True At The Time.

Which, in case you were wondering, is basically my synopsis of a fairly large proportion of what appears to have been going on within Günther’s book / world-view at large.

Or, to put it in Günther’s own [translated] words:

“My concern is not with any search for the so-called primitive in these religious forms, nor whether this or that higher idea is deduced from some lower stage of old Stone Age magical belief or middle Stone Age spirit belief (animism). I am solely interested in determining the pinnacles of Indo-European religion. My concern is to identify Indo-European religion at its most perfect and characteristic form, and in its richest and purest assertion—that completely spontaneous expression of the spirit in which primary Indo-European nature expresses itself with the greatest degree of purity.”

With anything that, whilst clearly being attested, runs counter to his preferred sentiment – well, his denigration of “Carl Clemen’s chapter on the ancient Indo-European Religion in his Religionsgeschichte Europas” as making “almost no contribution to our knowledge of Indo-European religiosity”, on grounds that “More than half of what Clemen cites as Indo-European religious thought, I regard as the ideas of the underlayer of Indo-Europeanised peoples of non-Nordic race.”

He then goes on to state :

“I shall confine myself to describing primary or essential attitudes of the Indo-Europeans, omitting all that they have expressed in their various languages, in their arts, and in the customs of their daily life in the early and middle periods of their development;” a situation which leads to such ridicularities as his seeking to declare of Odin that “Already one perceives in him the voice of an alien, non-Nordic race”, and his dismissal of Dionysus as an authentically Indo-European divinity because (I kid you not) he felt Dionysus to be insufficiently blond [it’s second page of chapter one] … in preference for, and I again quote: “much which has asserted itself in Islamic Persia and in Christian Europe in religious life”, the efforts of “great church leaders of both Christian faiths”, and a grab-bag of materials from “recent German poets. Examples of Indo-European religiosity can be found in Shakespeare, Winckelmann, Goethe, Schiller, Hólderlin, in Shelley and Keats, [etc.]”.

This is not, in other words, a serious study of Indo-European religion.

Which is not to seek to suggest, of course, that very cool and fundamentally ‘resonant’ elements might NOT be ever extracted from amidst much more modern sources – only that it is a very VERY peculiar sort of particularism which shall endeavour to insist upon THOSE being the legitimate places to look, even in spite of everything else going on therein … whilst entirely artificially looking to have thrown out as “alien” or whatever, things that we absolutely can show to be ‘core’ Indo-European belief rather than things absorbed in individual cultures from a localized non-IE periphery.

But I digress. And this piece is not intended to be some sort of expanded literature-review of the so-called ‘Race-Pope’s big ‘encyclical’. [Because seriously, I’d find myself having to do an escalating pile-up of annotations for seemingly every point the man makes pointing out what he’s purposefully omitted to mention … ]

Instead, what I had intended to say here is quite simple. Just because something might happen to come to you with a title like “The Religion of the Indo-Europeans” – this does NOT mean that it is necessarily a very good perspective on … well, the religion of the Indo-Europeans. Quite the contrary, in fact, as we can observe within this specific occurrence.

It is ALSO, as it should happen, not something so simplistically trite as “don’t take this guy seriously, he was an adherent of a certain political party in Germany in the 1930s/40s”. That would be a disservice to what I am trying to state here: which is that critical faculties are always required when delving into the work of others, and to suggest that the issue here is reducible down to Günther’s politics is to over-localize it entirely.

We shall demonstrate with a further exemplar.

A dominant theme within chapter 2 of Günther’s work is the opposition to the idea that the “Indo-European religiosity” possessed “any kind of fear”, most particularly “fear of the deity”.

This would surely come as rather significant news to the Vedic Aryas, who were very definitely a God(s)-Fearing People – hence why we encounter ‘Ghora’ and alike terms utilized in reference to the relevant Divinities. And the necessary distinguishments between the ‘Terrific/Wrathful’ Forms and the more Beneficent and Approachable Facings to the Gods thusly involved. And I shall restrain myself from an entire further article-length tangent concerning the many and various attestations in quite direct terms which we have upon this subject from not only the Vedic canon – but also those various other Indo-European textual suites which have come down to us … and which, funnily enough, are often quite pointedly coterminous in pertinent manifestations. Almost as if they’re not only describing the same Gods, but have come down from the same shared archaic textual / ritualine sphere. Funny, that.

Yet the curious thing is that this kind of sentiment – opposing the notion of ‘fear of Deity’, because it’s effectively spiritually unhealthy – is something which also shows up with quite some prominence amidst people who would almost certainly wish to very conspicuously assert themselves to be the opposites in every conceivable way of Günther.

In mid-2022, I somehow happened across a tweet from an apparently semi-prominent “Modern Traditional Witch [sic]”, Laura Tempest Zakroff, declaring that her sort “don’t fear [Gods]” on grounds that this was “Not really something considered to be a healthy trait in a relationship – divine or otherwise.”

It’s substantively the same sentiment.

Which is not, of course, to seek to suggest that that there is any underlying coterminity of political adhesion between Günther and this Zakroff person. Quite the opposite, in fact.

My entire point hinges around the fact that no singular political persuasion nor other such ‘human-level’ characteristic has anything like a ‘monopoly’ upon Bad Theology. Most especially not of “would very much like to believe other than what the traditions actually express” variety.

That is not an inherently ‘far right’ characteristic – nor is it an inherently ‘anti-far-right’ characteristic. It is, rather, a ‘human’ characteristic.

And the ‘core business’ for our theology is , in its essence and its tangible expressiveness, the intricate art of approaching That Which Is Above & Beyond Human Characteristic – and, not unrelatedly, Human Characterization.

Hence, one’s mortal preferences and proclivities are, strangely, almost the least important conditioner to the whole thing.

We Bow to Gods because it is the tradition – the Indo-European tradition.

We Bow to Gods because it is right and it is proper that we do so.

We Bow to Gods not because we are “slaves” – but because we feel respect, reverence, and gratitude unto They.

Worship, it should be remembered, is in its fashion “optional” – there are plenty of people out there who have actively chosen to eschew it and gone out to live amidst the mundane desert of the merely-sidereal.

And there are others, still others, who have chosen to go rather further than that, and who have benightedly declared themselves ‘adversaries’ to the Gods, traffickers with other such enemies of the Cosmic Order, and would-be usurpers and iconoclasts ‘gainst the Throne.

If one wishes to behold ‘slaves’ in all of this – then we need look no further. Slaves to their resentments, slaves to their demonic (and more powerful) invidious-puppeteer masters, slaves to the inevitability of their vanquishment. For such is the fate, sooner or later, of all those who would align themselves in enmity toward the Gods.

One does not term the Knight, upon bended knee afore his King, to be a “Slave” – quite the contrary, one terms him a ‘Champion’ for the most august figure in question.

So let it be in worship, and in reverence.

The most severely mis-aligned sentiments of certain ‘pontificating’ commenters actively resiled from, accordingly.

In closing, as we have so often said –

“We Bow Before The Lion Throne”

“Namaḥ Siṃhāsaneśvaryai”

As befits the Emperor & Empress of the Worlds Entire.

I believe the Icelandic Landnamabok also mentions bowing to the east to hail the rising sun.

LikeLike

would be interested in detail on that – I’d checked the Landnamabok I 9 citation that was given in the article i’d referenced but while it’s got something interesting, i’m not sure if the fact it isn’t seemingly bowing is a translation artefact or what.

LikeLike

I’ve been wondering about this in my explorations of ‘paganism’, as even “reconstructionists” who claim to base their practices on ancient sources and reputable historians promote this practice of raising the hands to look upward (and doing the opposite for the cthonic deities – looking downward with palms toward the ground), over any kneeling or bowing. On that note have you seen any evidence that DOES support those things standing with hands raised/lowered?

To me it also wouldn’t make much sense to do this as a reactionary idea against dualist-monotheistic sensibilities; as I was raised Catholic and remember the priest doing this all the time (raising the palms up and looking skyward as he spoke)… Ironically, while I remember a lot of kneeling in church, I do not remember actual bowing, which, to your point, rather reminds me more of cultural and spiritual practices across non-monotheistic swaths of Asia (rendering a bow to elders (or shrines)).

LikeLike