[Author’s Note: The following is an incomplete draft of an article that had been intended as an answer to a query received some three years prior with relation to an academic article looking at Apollo, Mithra, and an (Indo-)Iranian hailing upon a most remarkable trilingual stele from what was once Lycia.

I am perhaps unlikely to actually go back and properly finish it (some two years later!) – so provisionally make it available here. There may be some oversights within it due to the incomplete state, so caveat literator. [-C.A.R.] ]

Here at Arya Akasha, we take a certain measure of pride in responding to questions from our audience. Even if it takes us a whole year to do it. Such it was with the following enquiry from a gentleman, R.T., whose comment we shall reproduce in full below:

“Just read a good article about Apollo called “Apollo and Khshathrapati, the median Nergal, at Xanthos”. Point of the article was saying that the epithet Khshathrapati “Lord of power/dominion” usually said to be an epithet of Mithra is really an epithet for Apollo. Even though the two have been conflated with each other a lot it was still a good article. My question is, however, is this pointing to the fact that either Apollo or Mithra would be father of the Kshatriyas?”

And, because it’s actually quite an interesting subject (as well as because I feel a bit badly that his comment – and decent question – has been overlooked for *an entire year*), he’s getting a full-length article in response.

Which, because I’m … well … me – has wound up taking in quite an extensive suite of additional conceptry for Lycian Indo-European religion. Plus several things more. Buckle up. It’s going to be a bit of a ride.

Begins:

I am, for a start, a bit sideways-looking at articles that have a Mesopotamian non-IE deific in the title like that – because it often means somebody (the academic i mean) is about to try and assert a saliently IE figure and saliently IE features .. are not, and are best explained in a one-off occurrence of a non-IE influence. This is rarely the case when the situation is properly considered comparatively (i.e. we start noticing that the very same suite of correlate conceptry in *suspiciously* familiar patterning is to be found across a broad swathe of the IE spectrum, including in IE contexts entirely removed from the potential for having been the result of the specific claimed non-IE infusion in question).

But let us move forward to your substantive inquiry.

I am also cautious when it comes to the Iranic / Persian side of things being used as a ‘baseline’ to establish broader Indo-Iranic (let alone IE) comparanda. Which, in this case, is what is going on – and the reason for my caution is because the Zoroastrian sphere is, as is well known, ‘different’ to everybody else’s insofar as they had that significant interior ‘re-organization’ [to phrase it charitably] which featured various attributes being ‘reassigned’ (including to places that are .. rather .. not where things go for everybody else; or resulting in figures ‘missing’ key attributes, etc. – Verethragna, despite the name and despite the situation in both Armenian and Vedic spheres for a figure of cognate name, doesn’t slay a Dragon, for example; Mithra has a Vajra(-equivalent : ‘Vazra’ I think it is), unlike Mitra; you get the idea).

And further – we are in ‘interesting waters’ as applies one *specific* title such as ‘Khshathrapati” … because in order for this to ‘work’ as the basis of such an ‘interpretatio’ – it would be required for this to be exclusive to the Iranic .. well, Zoroastrian deific in question. And not thought of as a word that combines an attribute plus a lordship in relation thereto. And which might therefore be feasibly encountered in relation to other figures in other I-Ir or IE spheres. [Or, as it happens, potentially not actually pertaining, here, to a deity – but instead featuring a much more ‘mundane’ explication, instead … more on that in due course]

Generally speaking, Apollo ‘maps’ on to Rudra. This is uncontroversial, and we can point out various elements to prove this. Rudra *also* ‘maps’ onto Zeus – and we have demonstrated elsewhere how and why this situation of a ‘double-up’ has likely occurred. [Effectively, Apollo appears to have been a Luwian (etc. Anatolian IE) deific ‘encountered’ and ‘assimilated’ by the Hellenic sphere – albeit in a ‘subordinate’ role to Zeus, in a manner not entirely dissimilar to what we have attested for Sabazios / Sabazius et co. being ‘brought in’ as correlate with a ‘Son of the Sky Father’ rather than a ‘-Zeus’ proper, etc.; thus helping to explain an array of ‘double-ups’ and ‘co-occurrences’ in the mythology between Them, as we have detailed somewhat elsewhere]

So, what to make of this occurrence, here, then?

Well, for a start – the author (one Martin Schwartz) isn’t actually attempting to assert that the seeming-theonymic (or, at least, title) of ‘Khshathrapati’ encountered in the Trilingual Stele of Letoön at the center of all of this is the result of Mithra. In fact, quite the opposite – he’s actually seeking to pour some measure of cold water upon the idea in favour of something else entirely. We’ll consider both his actual inference along with a few other points of broader interest / saliency / digression herein.

He notes that “no comparable Avestan epithet [for Kshatrapati] is found for Mithra”, with the closest they’re able to come up with being one for Ahura Mazda that’s actually ” paitišə sax́iiāt̰ xṣ̌aϑrahiiā” … i.e. it’s two words, interspersed by a third, and once again showing that it’s .. well, not a codified theonymic, but rather two terms that may be applied to a deific (other than Mithra, as it happens) in question.

However, the author handily makes reference to the existence of our familiar Sanskrit “Ksatrapati’ in “several Brahmanas” … and whilst it *is* true that, at, say, SBr XI 4 3 11, we hear of Mitra as ” kṣatraṃ kṣatrapatiḥ ” … as we have seen, there exists no parallel Avestan construction for Mithra (or, apparently, in general), to directly connect this to.

The author went for “paitišə . . . xṣ̌aϑrahiiā” in reference to Ahura Mazda, instead. Oh, and also invoked Varuna as having a correlation with the “Ksatra” and so therefore suggesting a link to Mithra coz i) Mitra-Varuna , ii) Ahura Mazda as Varuna (which I disagree with for an array of reasons , for another time).

Except two can play at that ‘game’.

And I suspect I can play it rather better on my own ‘home turf’ !

Ksatrapati is *also* encountered at SBr V 4 2 2 (quoting VS X 17), wherein it’s a human king that is being imbued so as to *become* a Lord of Rulers [“King of Kings” is a modern idiomatic that has a not entirely dissimilar sense – although, as ever, Ksatrapati can be interpreted in other and more multifaceted fashion, as befits a Sanskrit ritual phrasing].

Further (and perhaps more germane to your inquiry), we *also* find at VS XIV 29 – “kṣatrám asr̥jyaténdro dʰipatir” … or, in a more full-throated context “kṣatramatrāsṛjyatendro’dhipatirāsīditīndro’trādhipatirāsīt” [c.f. SBr VIII 4 3 10] : the key point being here that we find ‘Kshatram […] Adhipati” (i.e. the ‘First Lord’, ‘High Chief’, of the Kshatra) – in relation to Indra.

And, additionally, we might draw attention to the situation at SBr IX 1 1 15 [and, for that matter, SBr IX 1 1 25] – wherein the “kṣatraṃ devaḥ”, in context, is the God [Who comes into being] is the Kshatra, is … Rudra. Who is, indeed, the Kshatra offered to in the next part to the verse.

We would also draw attention to Brihadaranyaka Upanishad [I forget what numbering the same verse is in the SBr] I 4 14: ” tadetat kṣatrasya kṣatraṃ yaddharmaḥ” – that is to say, “Dharma”, ‘Righteousness’, is the Ruler of the Ksatra(s). [Earlier, and i must emphasize this is somewhat ‘allegorical’ (insofar as various individual Gods aren’t ‘limited’ to being (of) ‘just’ one Varna; and also as the Varna-attribution in a given textual context might not be *quite* what and why one is anticipating) – it has the Maruts as Vaishyas a little later, after all [because They procure necessary resources, you see … not necessarily in the strictly ‘mercantile’ fashion … ]- I 4 11 has a list of the “devatrā kṣatrāṇi” [‘Kshatra’ among the Gods] : “indro varuṇaḥ somo rudraḥ parjanyo yamo mṛityurīśāna iti ” … “Indra, Varuna, Soma, Rudra, Parjanya, Yama, Mrityu [Death], Ishana, it is”. Interestingly, Parjanya and Ishana [c.f. in particular SBr VI 1 3 15 & 17, for instance] and Soma are well attested Rudra ‘Aspects’, ‘Theonymics’, ‘Facings’, ‘Qualities’, in the Brahmanas etc.; Mrityu shows up as a Rudra linked ‘Aspect’ [One of the Eleven in some texts], although that’s usually later and we can also take this in other ways [e.g. Yama]

And it is most interesting to hear Ishana mentioned there – as Isana [ Īśāna ] itself means ‘Ruling’, ‘Reigning’ … and, intriguingly for our purposes herein, is prominent in linkage with … The Sun. That’s rather directly how SBr VI 1 3 17 puts it – that Rudra is declared Ishana , Ishana is the Sun (Aditya), and Ishana (Ruler) links with this, indeed, due to the Sun reigning [widely] over all. How about that. [note: this is most definitely not the only ‘Solar Rudra’ strong co-occurrence, it is just rather convenient herein]

Now, importantly – the article you have referenced makes mention of Apollo having ‘originally’ been an ‘Underworld God’, and thusly explains the ‘Chthonic’ saliency seemingly in evidence in this area for Him. We do not (necessarily) disagree [subject to my usual extensive caveats about the ‘Chthonic’ vs ‘Olympian’ duality typology making for … a grand mess due to the actual Classical theology *not really working that way* [c.f. Zeus Meilichios causing headaches for modern-day scholars for precisely this reason] and working *less* that way the further back you go into the mists of Proto- pre-history] … but good *grief*

Take a look at this paragraph:

“Apollo’s sojourns in the underworld, his close relation to obscurity and death, and his shooting arrows of disease, as well as his healing, are features which make him parallel to the Mesopotamian underworld god Nergal. Furthermore, both Apollo and Nergal are represented by ravens, and are associated with palm trees, snakes, and lions”

Rudra, as you may have figured by now … has *quite* some relation to Death, shoots “arrows of disease”, brings “healing”, is associated with Ravens [c.f. AV-S XI 2 2; and, of course, Odin], and while I’m not sure about *palm* trees specifically, most definitely does have arboreal associations [‘in trees’, indeed, per relevant archaic scripture – ‘Vrksanam Pataye’, ‘Lord of Trees/Wood(s)’, as the Sri Rudram has it], strong ‘snakes’ linkages, and ‘lion’ linkages, as well !

So, our position is quite simple.

This guy writing is basically trying to ‘force’ a triangulation with a Mesopotamian deific for Apollo in Xanthian situation , so as to have … not so much ‘Lord of the Kshatra’, as in ‘Kshatriyas’ – but more as in ‘Lord of the Dominion’, and with a rather *particular* Dominion in mind …

To quote him:

“This confirms that Khshathrapati “Lord of the (underworld) City/Realm” (a descriptive epithet with the tabuistic advantage of serving to avoid naming the sinister god) was modeled after Nergal.”

This is … I’m not going to say “idiotic”, but certainly “unnecessary” in the extreme.

Why? Because i) there isn’t an actual statement in the inscription in question to directly support that ‘Underworld’ (or Rulership thereof) is actually intended by the inscribers. You can certainly *infer* it [no pun … by me at least … initially intended] based on context, and more on that in a moment; but a better understanding is also rather immediately apparent …

ii) in order to *get* an Underworld / Rulership thereof association for Apollo, it is *absolutely unnecessary* to suggest that this has to be the result of Mesopotamian Nergal cross-pollinative influence. Instead, we would observe that a) the relevant underlying IE deific complex has such linkages *anyway* (c.f. Odin with Valhalla etc.; interestingly hailed by Saxo Grammaticus as ‘Orci Plutonem’ .. Pluto of Orcus (and we might tentatively contemplate an ‘Oath’ association being there also); and, more obviously, Rudra in such decidedly Sepulchral associations and coterie – as well as the fact of Dis Pater (Pluto, Hades, et co) … well, it’s right there in the name viz. *Dyaus Pitar*, isn’t it … ); b) that the notion of an ‘Underworld Sun’ is *also* strongly in evidence, including quite particularly in the IE Anatolian sphere (the Hittite Goddess of Such springs instantly to mind – as does Hekate , speculated to be rather linked thereto .. c.f. Freyja with Folkvangr, Aditi ruling over the Pitrs, Persephone, etc. ), with this tending to be linked to a Goddess figure that maps handily to Ambika (Rudra’s ‘female counterpart’, we might succinctly summarize – it’s a bit more complex than that , but anyway) [this point is *particularly* relevant given the *actual invocation* on the stele in question – more on that in due course]; c) an array of associations quite present in the Classical comparanda for Apollo – like those occasions wherein a corpse is ferried away or protected, or the Moirae engaged by Him with a view to altering the circumstances of a lifespan’s termination (i.e. securing a longer span of days for the favoured), or enlisting Aeacus (better known for other work, perhaps) as assistant (tellingly, ‘wall-building’ – alongside with Poseidon).

iii) his argument hinges, effectively, upon the idea that the ‘Xsathrapati-‘ [no, that isn’t the correct text, but it’ll do ..] is a calque for a title of Nergal as ‘Lord of the Great City’ [this being the Realm of the Dead]… without stopping to consider that there’s a *much* more immediately pertinent suite of conceptry to go with a ‘Kshetra- Pati’ style figure (and of pervasively Indo-European attestation – more on that in due course) which should seem to better fit this *specific* invocatory context anyway. [In terms of your question, he *does* resile from the notion of Mithra as being meant by the title in this occurrence – noting that, per Yasht 10 56, one is supposed to address Mithra *only* by Mithra’s “proper name”]; because –

iv) he effectively *really* wants there to be a non-/pre-Zoroastrian Iranic deific (well, worshipped by a Magian Mede holdout of sorts) that’s actually the aforementioned Mesopotamian Nergal incorporated into the Median sphere of worship. Rather than considering, say, *another* and endogenously Indo-Iranic deific that just so happens to be a) strongly correlated with the concept underpinned in that term ‘Khshathrapati’, b) likewise with regard to quite an array of the other comparanda that’s salient (and which he seeks to bring up as correlating between Apollo and Mesopotamian ‘Nergal’), and c) Who’s actually attested as worshipped amidst various non-Zoroastrian (or, at least, not-as-Zoroastrianized) Iranic groups into the bargain.

v) or, alternatively – and more plausibly – the actual archaic Lycian deific underpinning all of this (no non-attested Median holdout necessary) having the requisite elements already and endogenously, with the Iranic titling not being more than just exactly that by a scribe doing the translating – and any significant coterminities with our aforementioned Indo-Iranic deific being the result of a similarly archaic Indo-European religious sphere having a recognizably similar deific expression thereto.

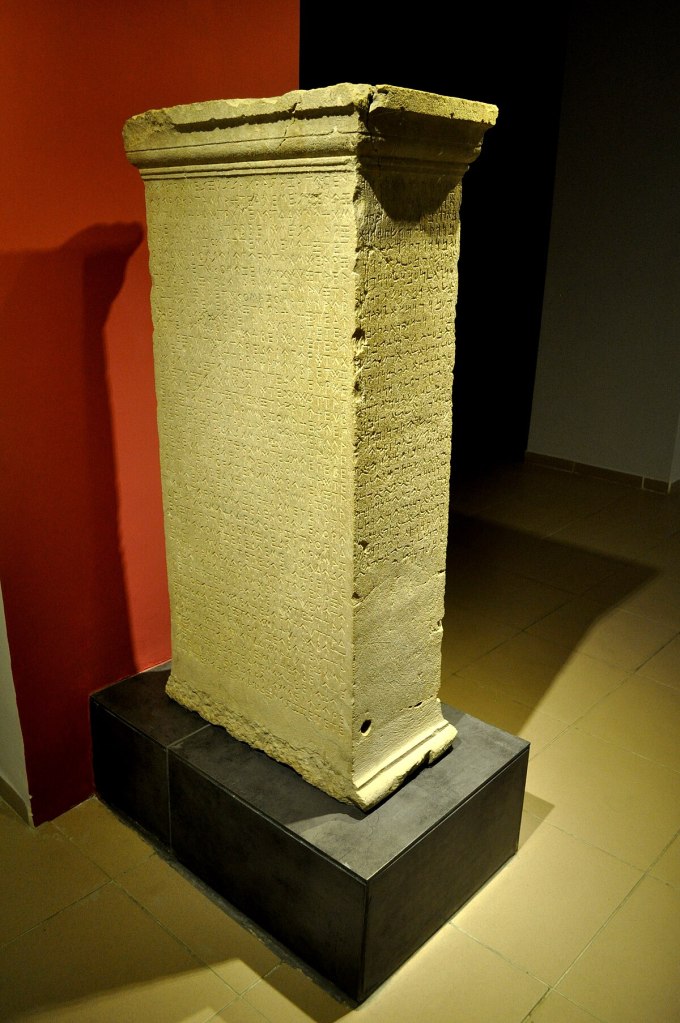

So anyway … let’s take a look at this term – Khshathrapati – in its *actual* context … namely, the Aramaic portion of the famed Trilingual Stele inscription at the Letoon temple complex (the other two languages being Lycian A and Ancient Greek).

Now what it is, is an inscription stating that a (to *heavily* summarize) ‘sacred space’ has been erected (with this being a joint undertaking of two settlements and groups, it should seem), devoted in particular to two rather enigmatic deifics (Whom we shall not get into here) that are seemingly both Gods … and also, rather pointedly, *King* figures, with this sacred space being clearly demarcated as the property of these two ‘Kings’ ; the remaining text concerning a Priest appointed, what’s supposed to be offered annually as well as monthly by the two groups, and other such regulations … with these having been sealed via sacred oaths.

Where things become of interest for us are in the last few lines – where we encounter the rather dire ‘guarantees’ (and religious ‘Guarantors’) for the whole artifice:

In Greek, these are these (τῶν) [assumedly the aforementioned two ‘Kings’ as] Gods (θεῶν) , Leto, Her Descendants (ἐγγόνον) [i.e. Artemis & Apollo], and ‘the Nymphs’.

In the Lycian, it is much the same – the [aforementioned] Gods (maha͂na), the ‘Pñtreñni’ [a complex term we may briefly look at in due course] [, ?] Mother (ẽni) of the Complex/Sanctuary [Sacred Enclosure] (qlahi ebijehi) [Assumedly, Leto], Her Children (tideime) [inferentially Artemis & Apollo], and to the Eliyana [‘Nymphs’] ;

In Aramaic, it’s considerably truncated overall relative to the other two inscriptions, but helpfully, things are more overtly ‘spelled out’ : and we have Leto, Artemis, ‘Ḥšatrapati’, and ‘the Others’ (‘ˀḥwrˀnyš’) [i.e. ‘Nymphs’ – there not being a ready analogy for these in Aramaic and the Semitic sphere from whence the language and its scribe had arrived] .

Now, the ‘Nymphs’ are straightforward – these are the Rudraganikas , or various other such terms for that fearsomely formidable clade of wild-haired and terrific, howling female figures we find in the Retinue(s) of Rudra per AV-S XI 2 etc. (and c.f. my work ‘reconstructing’ such a clade in more pervasively Indo-European occurrence elsewhere – including the otherwise inexplicable ‘Amazonius’ (or ‘Amazonios’) epithet of Apollo encountered at Pyrrhichus per Pausanias III 25 3; where we also encounter Artemis Astrateia – and also c.f. Dionysus in command of an Amazon legion, per Diodorus Siculus … effectively the same as the Maenads in terms to our typology … ish], Who are, Themselves, of quite eminent ‘Funerary’ and ‘Sepulchral’ (well, ‘Crematorial’) associations – and Who are, of course, correlate with the Matrikas (and Yoginis) of later attestation (and terror).

As a brief aside, Schwartz suggests that the term rendered as ‘Others’ above from the Aramaic inscription – W’ḤWRN (or WˀḤWRN ) – *should*, in fact, work out as ˀḥwrˀnyš … effectively Median ‘Axurānīš’ , that is to say Avestan ‘Ahurānīš’. As one might expect, these are correlate to ‘Ahura’ in both language and attestation – being majorly occurrent at Yasna 38 as a group of ‘female companions’ or perhaps ‘wives’ of *the* Ahura (or, perhaps, Ahuras, plural), and inferentially Waters-spirits. There is a *claim* that these are some sort of ‘direct map’ for Varuṇānī … and on the surface, it sounds credible. Except for the rather important point that Varuṇānī is a *singular*, not a plural or collective – and I have not yet run across any such ‘Varunani’ in plural formulation except amidst Zoroastrian-oriented scholarship claiming such a thing to exist in the Vedic sphere (it doesn’t). [There *are* some occasional mentions for Varuna having several Wives , identified with particular Rivers or Water(s) and spoken of directly by Names or in collective as ‘Waters’ – e.g. TS V 5 4, which has ” ā́po váruṇasya pátnaya” , ‘The Waters [Ap-] were Wives [Patnaya] of Varuna’, but as we can see this is not some sort of ‘Ahurani’ collective designation , and I am unsure that I have encountered any ‘Asuri’ nor ‘Asuryā’ [‘Asura’, in feminine formulations] in a grouping of this sort; but I digress] .

Personally, I am not sure that it makes much difference. The deifics honoured at the place and in the inscriptions are quite clearly not Zoroastrian figures, but rather are the Anatolian Indo-European deities that one ought, presumably, expect and anticipate given the nature of the settlements involved as Lycian and Xanthian polities. Albeit with Three (and Retinue) of these – Leto , Artemis , and that most famously ‘Lycian’ hailed figure, Apollo [ λύκειος (Lykeios – Lycian), and even Λυκηγενής (Lykegenes – Lycian-Born), etc.] being of quite significant Hellenic overlay and saliency. Therefore, the Aramaic renditionings, whilst useful (insofar as these lines actually indicate the *specific* Children of Leto … just in case there might be some *other* Children (whether direct or adoptive or figurative) for Leto in Her more archaic Anatolian perception. Wolves, perhaps … ‘Temple Wolves’, potentially, even 😛 ? ) ought not be taken as determinative. After all – as we have seen viz. their trouble with ‘Nymphs’ or ‘Eliyana’, the Aramaic textual application is certainly not averse to substituting in potentially rather ‘loosely fitting’ terminology where its own grasp (whether lexical or conceptual) would otherwise prove lacking. This should assumedly go double as applies those potential scenarios wherein a twofold layering of ‘difference’ is thusly entailed – first the Aramaic textual one itself, but second the Zoroastrian(ish) Imperial Persian perspective which it sought to communicate and apply. The latter may, of course, still be an Indo-European-originated sphere … but is not from the same (sub-)family / branch as either the Anatolian or the Hellenic, even afore the ‘particular’ situation of the Zoroastrian religious corpus of conceptry is taken into consideration (i.e. that bit wherein quite an array of the ‘usual / established elements’ have wound up being ‘editorialized’ or in some cases outright suppressed … particularly as applies Roudran deific elements – something of quite some overt pertinence when we are speaking, of course, about Apollo ! ).

In fact, Schwartz’ argument, if I am understanding him correctly, is even more ‘indirect’ – namely, that what has effectively resulted viz. this ‘Khshathrapati’ situation for a figure identified with Apollo at Letoon, is not the result of a Zoroastrian ‘labelling’, nor the direct transferrence of a more conventional Indo-Iranic entitling … but rather, is a translation (both linguistically and culturally / theologically) of a Mesopotamian deific. As rendered via Aramaic with occasional Iranic loan-wording. (And with, it must be said, the most interesting supposition that the ‘ḥštrpty’ in question is, in fact, in the *instrumental* case rather than nominative or vocative; we may, ourselves, speculate as to the potential saliency for this in due course)

Now, Schwartz’ reasoning goes like this. In fact, I’ll just quote it verbatim:

“The larger context, in which Khshathrapati is mentioned alongside Artemis in series with the Abyss, Leto, and the Nymphs—all chthonic— would point to a chthonic aspect of Apollo which is reflected in his translation as Khshathrapati. Now, Apollo in western Anatolia had chthonic associations due to his presiding over healing via incubation in artificial grottoes called Charoneia (or Plutoneia).

[…]

Apollo became a sun-god only gradually, originally being an underworld god. The foregoing local circumstances would have tended to prolong Apollo’s older chthonic nature, his being understood as a sun-god in the Greek world gradually taking place from the 5th century onwards (Burkert 1985, 149).

[…]

Apollo’s sojourns in the underworld, his close relation to obscurity and death, and his shooting arrows of disease, as well as his healing, are features which make him parallel to the Mesopotamian underworld god Nergal. Furthermore, both Apollo and Nergal are represented by ravens, and are associated with palm trees, snakes, and lions. Both Apollo and Nergal, in aspects of their myths, represent the sun in the netherworld.

[…]

Now, Nergal’s name goes back to a Sumerian phrase “Lord of the Great City” (Wiggermann 2001, 218–19), which refers to a durable Mesopotamian conception of the realm of the dead as a large urban settlement. This points to the conception of Nergal, as lord of such a realm, being calqued in Iranian as Xšaθrapati- “Lord of the City” (xšaθra- > “city” in West Iranian).

The necessary evidence for an Iranian netherworld god *Xšaθrapati- comes from Armenian materials conveniently brought together in Russell 1987, 330–32. […] What concerns us is Russell’s data on sahapet, a supernatural being or category of such beings. The citations from the 13th cent. Oskiberan, in which various pagan divinities are detailed as šahapet-s of trees and vines, attest a connection with vegetation consonant with an ancient chthonic god. The much older citations from the Classical Armenian Agathangelos and Eznik indicate that šahapet is associated with tombs and the netherworld, as well as with aquatic and terrestrial reptiles, in particular with serpents, whose forms the šahapet can assume, leading men to abandon God for worship of snakes. The latter details, which imply the worship of a šahapet intimately connected with snakes, recalls the iconography of Nergal in the Parthian period at Hatra, with snakes all around the god and being part of his accoutrements. We have here evidence of Nergal = šahapet, which must derive linguistically from *xšaθrapati-, like šahap < *xšaθrapa– “satrap,” hazārapet < *hazārapati- “chiliarch,” etc. This confirms that Khshathrapati “Lord of the (underworld) City/Realm” (a descriptive epithet with the tabuistic advantage of serving to avoid naming the sinister god) was modeled after Nergal.”

To put it bluntly, “No”.

We’ll start with the Armenian point. Russell, the gentleman Schwartz is referencing, had this to say upon the matter:

“But in his otherwise meticulous survey of the data he neglects to mention that there is, however, a very prominent Armenian Nergal. This is Tork‘ Angeł, i.e. Tarḫundas-Nergal. In the fourth century AD, Shapur II sacked Armenian Arsacid tombs in the region of Angeł Tun (Gk. Ingilēnē), which bore the name of this being. He seems to have had chthonic associations, then, but Armenians did not identify him with Apollo. They saved that syncretistic association for Mithra, probably because of the common and prominent solar aspect of the Greek and Iranian divinities; and the Greek inscription identifying the cyclopean statue of Mithras on the great platform before the hierothēsion of Antiochus of Commagene on the heights of Nemrut Dagh calls the god Mithras-Apollo-Helios-Hermes. The Armenian Nergal is not referred to anywhere as a šahapet. […] But, like the Švot, he is imagined as a powerful giant with frightful features, hence Movsēs Xorenac‘i’s Volksetymologie from Arm. an-geł, “not beautiful”— and the Armenian Patmahayr, “Father of history”, adds that Tork‘ was known to heave, Cyclops-like, huge boulders at the ships of invaders. So in a way he was, also like the Švot, a protector of the home writ large.”

Now at this point, I shall restrain myself (with some difficulty) from going off on a fairly massive digression as to the likely *proper* ‘Interpretatio’ for salient Armenian deifics & linguistics here in comparative Indo-European, Indo-Iranic (and especially Vedic) terms. Suffice to say there’s some really fascinating elements that we *do* intend to return to consider at a later date. Roudran ones, in specia. To, no doubt, nobody’s especial surprise. [Also, as a brief – and I *do* mean *brief* – side-point … the rendering of ‘An-Geł’ as “not beautiful” – whilst certainly *one* way to take it , is perhaps lacking a certain something. The impression one gets from reading over the literature is instead more of a ‘Terrific Appearance’ sort of vibe: ref., of course, the ‘Ghora’ [c.f. “Gorgoneion”] Facing to Rudra; and certainly going rather nicely with the ‘Fierce Gaze’ (Armenian: “džnahayeac‘”) quality of this ‘Boulder’-throwing (ref. Sanskrit ‘Aśman’, Meteor Bombardments, etc.) Protector/Defender figure. Although an intriguing and not-necessarily-exclusive interpretation has ‘An-Geł’ instead as something closer to ‘Non-Visible’ … in the sense of ‘Hades’ (which is literally what the term likely means). We would recall our own work viz. PIE *ḱel- in relation to the ‘Veil’ between the Worlds of the Living and the Dead – as well as, of course, how this is the similar root underpinning the ‘Ghora’ visages of the Wrathful Facings of relevant Deifics (c.f. Kali, the Cailleach, certain terms for Demeter Erinys / Demeter Melaina, etc.) ; with the ‘Corpse-like’ descriptions prevalent in some cases being most pertinent, also … BUT AGAIN, I DIGRESS]

The point is – the Armenian situation, such as it is, does not actually supply “evidence of [Mesopotamian] Nergal = šahapet”. And it is also a bit curious to be speaking of “Nergal in the Parthian period at Hatra” – an era in which the Mesopotamian Nergal in question was being ‘Interpretatio”d with Hellenic *Herakles* in any case (as can, as it happens, be pretty clearly seen in some of that seriously serpent-incorporating “iconography of Nergal in the Parthian period at Hatra” that Schwartz happens to mention, in fact) .

This was not merely a situation of ‘Interpretatio Babylonica’ for the Hellenic (and it *is* pointedly Hellenic rather than broader ‘Classical’, for the most part – there’s only a bare trace of a Latinate ‘Hercules’ to go with, interestingly enough) – but *also* engaged the Persian / Iranic sphere. How can we tell? Inscriptional evidence referring to this Herakles-Nergal syncreticism via the title of ‘dḥšpṭʾ’ – which, per Dirven (referencing Tubach), should work out as ‘Dahashpata’, or ‘Lord of the Guards’ . Which does not , in and of itself , render axiomatically impossible the idea of a different ‘Interpretatio’ arising elsewhere for the same deific.

Although that is not really why I would have to say that the forcible introduction of Mesopotamian ‘Nergal’ into proceedings by Schwartz back at the sanctuary of Letoon is so saliently ‘unnecessary’.

Rather – it is because, to put it quite bluntly, *it’s fairly blatantly unnecessary*.

And, to explain that which I intentionally mean by that … let’s arcen back for a moment to that which Schwartz thinks he’s uncovered as the trenchant results of all of this.

Effectively, he claims that the figure hailed as ‘Khshathrapati’ here is a “patently non-Zoroastrian” deity of the “Magians as part of their old religion”; that is to say, that this is *pre-Zoroastrian* deific, the active acknowledgement and worship of which has somehow wound up holding on even into Achaemenid times as, as he puts it, “old local traditions on the periphery of the empire”.

With the identity of the deific in question allegedly being Mesopotamian Nergal due to “the northern Mesopotamian history of the Nergal cult, and the origin of the Armenian Šahapet.” And then attempts to buttress all of this by claiming that “Linguistically, too, xšaθrapati- conforms to Median rather than Old Persian phonology […] Specifically Median phonology in fact characterizes ˀhwrˀnyš = Axurānīš.” And seeks to explain just what an ostensibly Median (albeit more archaically of Mesopotamia) deific is doing all the way over in Western Anatolia, as being presumptively ” due to the foundation, under Cyrus’ dispensation, of the city of Xanthos by Harpagos the Mede and his retinues, including troops and their families, inevitably with a representation of the Median priesthood, i.e. Magi.”

Working our way backwards on this one, we can do little better than quote Russell’s response to all of this:

” Even if ḥštrpty is to be considered pure Median, rather than a loan into Old Persian, which latter possibility is far more likely— not least when one considers that no documentary attestation of Median, not one inscription, is known to exist— there is no particular reason to suppose that this “gemeiniranisch” form, adopted like some other terms of rank by the Achaemenian Persians, either reflected or was intended to convey a specifically Median religious belief.

Nor, indeed, would one expect an identifiably distinct Median presence to be asserted by the middle Achaemenian era amongst the Iranian nobility of Xanthos or elsewhere in central and western Anatolia, who hailed from diverse satrapies but served a Persian king. There is almost as little evidence of the religious beliefs and practices of the Medes as there is of their language: it is impossible for the time being to reconstruct these in any but the most hypothetical way. Though the Medes dwelt in continuous proximity to the older, greater civilizations of Assyria and central Mesopotamia, the few sources we have are silent about any Mesopotamian presence in the Median pantheon, whatever other stars there might have been in that mysterious constellation.”

It is immediately following the above that Russell launches into his earlier-quoted critique of Schwartz’ assertions viz. “the origin of the Armenian Šahapet” and alleged “evidence of Nergal = šahapet” in relation thereto.

So where does that leave us?

Well, again – to put it rather bluntly … observing that Schwartz’ conclusions must now render via his capacious ‘enthusiasm’ that which they cannot seemingly substantiate via actual evidence.

And, more to the point, noting that where Schwartz *wants* to get to is, in part, somewhere he needn’t have sojourned out into the archaic and pre-Indo-European sands of Sumeria in order to grasp at.

No, if Schwartz were to venture in search of a ‘pre-Zoroastrian’ deific Who *just so happens to have* a strong congruity with Apollo and various of those essential identifying other features which he had staked out for us … well, it shall come as no surprise that we would instead have thought Rudra, or (more accurately) an Iranic co-expressive thereof, should be the template. After all, we *know* that He was known amidst the non-/pre-Zoroastrian Iranics … the Sauruua / Sarva (Śarva) identified amidst the Daevas is strong proof as to that, particularly when one considers their correlate viz. ‘Ishmin’. And we also have similar ‘submerged’ Shaivite conceptry when we consider what they recalled of that famed ‘archer’ correlate, Tishtrya (see my previous commentary upon this subject published just recently for more detailing) – which should even correlate with Apollo when considered in light of that detail given via Apollonius of Rhodes as to Sirius and the ending of Drought [Argonautica II].

Indeed, if we take a brief examination of Schwartz’ own rubric for attempting to align Apollo & Nergal:

“Apollo’s sojourns in the underworld, his close relation to obscurity and death, and his shooting arrows of disease, as well as his healing, are features which make him parallel to the Mesopotamian underworld god Nergal. Furthermore, both Apollo and Nergal are represented by ravens, and are associated with palm trees, snakes, and lions. Both Apollo and Nergal, in aspects of their myths, represent the sun in the netherworld.” And, following this, the inference viz. his ‘Xšaθrapati’ as ‘Lord of the City’ as, and I quote: “Khshathrapati “Lord of the (underworld) City/Realm” (a descriptive epithet with the tabuistic advantage of serving to avoid naming the sinister god” …

… these are all, I kid you not, fairly definitively Roudran features (with a potential caveat on ‘sojourns in the Underworld’, admittedly). “Close relation to obscurity and death” – check. “Shooting arrows of disease” – very *much* check. ‘Healing’? Absolutely. Ravens? AV-S XI 2 2 has us covered.

The prominent usage of “descriptive epithet[s] with the tabuistic advantage of serving to avoid naming the sinister God”? Oh you’d better *believe* ‘Check’. Start with ‘Shiva’ and work your way backwards – the Brahmanas go to town with this for ritual phraseology [c.f., for instance, Ait. Br. III 34, Haug translation: “he ought to use the word rudriya instead of rudra, for diminishing the terror (and danger) arising from (the pronunciation of) the real name Rudra”, “[ ( ] should this verse appear to be too dangerous) the Hotar may omit it and repeat (instead of it)”, “The deity is not mentioned with its name, though it is addressed to Rudra, and contains the propitiatory term śaṃ. […] By repeating that verse the Hotar worships Him (Rudra) by means of Brahma[na] (and averts consequently all evil consequences which arise from using a verse referring to Rudra).” , the earlier commentary [i.e. Ait. Br. III 33] seeming to go out of its way to use nondescript almost non-hailings such as ‘Bhutavan’ (‘One Who Has Come Into Being’), .. .and before I get *too* carried away, let’s just quote Eggeling’s annotation on SBr I 7 4 3 (which he translates as “The Gods then said to this God Who rules over the beasts […]” – “The construction here is irregular. Perhaps this is part of the speech of the gods, being a kind of indirect address to Rudra in order to avoid naming the terrible god.”, etc. etc. etc. One would look in vain for the *direct* Name of Rudra even within some of those certain Vedic Hymnals or verses therein that are still, nevertheless, to Him – instead only finding ‘Titles’ or ‘Descriptors’, ‘functional theonymics’ … Vastospati within the context of RV VII 55 springs instantly to mind for reasons that shall prove readily apparent within due course]

Palm trees I am unsure about – but *Trees* … the Lord In Tree(s) / Wood(s) is most definitely within the Sri Rudram (‘Vrksanam Pataye’, alongside, one might suggest, ‘Sthapataye’ – Lord of the Post); Snakes are found recurrently within the Roudran associations (including via the Serpentine / Draconic *Forms* of Rudra); Lions might present a slightly greater challenge, although RV II 33 11 *does* have Rudra as a fearsome beast-of-prey of the forest, with subsequent scripture definitely including ‘Lion’ within the scope of His Mighty Forms (c.f the extolling of Rudra in the Anuśāsana parva of the Mahābhārata, so Nyāyaratnasiṃha tells me). We also have Rudra as the Sun, quite prominently, at various places – and, rather usefully, the aforesaid situation of Rudra as ‘Kshatra’ Deva and also as *Kshetra* Deva / Lord [c.f. VS XVI 18 (and thus also the Sri Rudram) – kṣétrāṇāṃ pátaye].

It is the latter that is the most useful here – Kshetra-Pati … or, as we would say of Bhairava (inter alia): ‘Kshetra-Pala’, perhaps.

However, whilst it might prove vaguely tempting to seek to connect what Schwartz is going for here viz. his ‘City of the Dead’ annotation to the Afterlife – or, for that matter, to the Cremation Ground (Smashana – wherein Rudra is, most definitely, the Lord (to be) Encountered Therein … ) – I do not *necessarily* agree that that’s what the much-discussed ‘Khshathrapati’ of the Trilingual Inscription’s Aramaic facing had *actually* intended to convey.

Rather, a different prospect presents itself. Or, perhaps – we shall see – Herself.

To quote myself from above – the relevant lines as presented on each facing are in relation to the ‘guarantors’ of the place and its custom. Specifically, anybody breaching these by aggressive act … well, they would be held responsible to the :

“In Greek, these are these (τῶν) [assumedly the aforementioned two ‘Kings’ as] Gods (θεῶν) , Leto, Her Descendants (ἐγγόνον) [i.e. Artemis & Apollo], and ‘the Nymphs’.

In the Lycian, it is much the same – the [aforementioned] Gods (maha͂na), the ‘Pñtreñni’ […] [, ?] Mother (ẽni) of the Complex/Sanctuary [Sacred Enclosure] (qlahi ebijehi) [Assumedly, Leto], Her Children (tideime) [inferentially Artemis & Apollo], and to the Eliyana [‘Nymphs’] ;

In Aramaic, […] we have Leto, Artemis, ‘Ḥšatrapati’, and ‘the Others’ [i.e. ‘Nymphs’ – there not being a ready analogy for these in Aramaic and the Semitic sphere from whence the language and its scribe had arrived] .”

Now, our area of interest here is chiefly the Lycian text. Given that the culture in question at the site was, specifically, of the Lycian sphere – even despite a Hellenistic ‘overlay’ and ‘interplay’ observable (and, for that matter, the potential for Carian relation)… it seems logical to take, as it were, the Lycian text as being the ‘definitive’ one that the other two are ‘translations’ (or, at least, rough precis) of (not least because the two ‘Kings’ specified as Divinities related to the site are observably Lycian and not Hellenic). Although we can also, most definitely, make ample utilization of certain elements from the Hellenic and Aramaic sides to help us to ‘interpret’ things therein.

Intriguingly, the Lycian text *does not* do us the specific service of rendering the exact and familiar theonymics as the Hellenic and Aramaic texts do to varying extents – we do not observe a ‘Leto’ (as seen in both the Aramaic and Ancient Greek; with the Aramaic, intriguingly, using the *Greek* form rather than a Lycian one, as noted by Valero), nor do we observe an ‘Artemis’, which is (as “ˀRTMWŠ”) *only* observed in the Aramaic. We also do not, in *any* text, observe an Apollo – that has been inferred due to i) the situation of Leto’s ‘Descendants / Children’ [and assuming that this does not refer to another sort of descendant], ii) the logical inference that Artemis’ mention in such a context should prove incomplete without Her Twin, Apollo, also in residence (and, quite literally, ‘in residence’, given that along with the Temples to Leto & Artemis, the third major siting – that, as it should happen, the Inscription was found relatively near to, is that of a Temple to Apollo).

Yet it occurs to me that the archaic Lycian religious situation may not have been quite so uncontroversially coterminous with the more familiar ‘high Hellenic’ dominant picture of the Classical Pantheon that has come down to us. We have sought to demonstrate some scope for that in our previous works – and not least, of course, via direct comparanda with the Vedic sphere to show how things might have ‘diverged’ here and there. Particularly when they became (re-)incorporated within the broader general Hellenic milieu.

The oldest temple at Letoon should appear to be that of Artemis – this being joined by, in order, Apollo’s and Leto’s. A strange thing for what is *ostensibly* a site oriented *toward* Leto.

Except, of course, if we note – as Dr Eric Raimond does – that the situation of Artemis, archaically, in fact appears to be that of ‘Chief Goddess’; or my own observations around not only Artemis in relation to, say, that Divine Counterpart of Rudra (ref. Ambika – viz. SBr II 6 2 9 / Taitt. Br. I 6 10 4 , etc.) … but also, perhaps unexpectedly, in roles otherwise concordant with those of Rudra Himself (for instance – that which She does to a certain Prajapati-correlate via Her Bow).

There is quite a bit more which we *could* say upon this matter, but for reasons of space we shall leave it for the future. And instead simply observe the following:

The presumption hitherto has been that ‘Ḥšatrapati’ ought stand for ‘Apollo’. Yet the *actual* terminology in the Lycian that stands for the Presiding over the Precinct – is feminine. That being the ‘ẽni’ (Mother) of the ‘qlahi ebijehi’ (Sacred Enclosure). And, *potentially* at least, also the Pñtreñni encountered in the same line. Which *may* in fact similarly constitute a ‘Mother’ (in this case, ‘-eñni’) as argued by Vernet (inter various alia); and which most certainly *seems* to be a rather decidedly ‘Leto’-associated element, per Bryce’s observances as to the subject … who had noted something of a pattern for Pñtreñni in relation to ‘qla’ or ‘ẽni qlahi ebiyehi’, encountered at an array of locales, and also in defence of Lycian Tombs. We do not intend to get into the rather … vexed situation of just what ‘Pñtri’ may have originally been intended to entail. Suffice to say there are a few different (or semi-overlapping) prospects. One of which, rather interestingly, per Carruba, appears to be something along the lines of ‘Chthonic’ or ‘Underground’, derived from *epñteri. Although elsewhere he seems to speculate ‘City’; and this aligns also with Bryce’s comment viz. *pñtri as a ‘territorial unit’. But we digress.

In essence – the situation of ‘Leto’, and even (to a lesser extent) ‘Artemis’ seems something of an ‘Overlay’ upon the archaic Lycian religious situation extant at Letoon. This being the Goddess known as Ẽni Mahanahi – the Mother of the Gods (and we would note with some interest the comment encountered at Herodotus I 173 of the Lycian custom – “they take their names not from their fathers but from their mothers, and when one is asked by his neighbour who he is, he will say that he is the son of such a mother, and rehearse the mothers of his mother.” [Godley translation] Why? Because if one considers, say, the Adityas relative to Aditi – or the Tuatha Dé Danann [‘Tribe of the Gods of Danu’] relative to Danu … well, it should seem quite the Divine custom, as well, amidst the Indo-Europeans); with this figure later acquiring the name ‘Leto’ – assumedly upon the basis of Lycian ‘Lada’, that means ‘Wife’, ‘Lady’ (assumedly c.f. Hellenic ‘Leda’; and perhaps also Slavic Lada / Lado), perhaps (per Adams) from a PIE *lehₐd-ro- meaning ‘Dear’. We have earlier considered elsewhere how and why such a generic ‘Wife’ term might arise in application to Her with relation to the situation of Chhaya – although I also might ponder the idea viz. ‘Despoina’ as dread hailing encountered elsewhere. That is to say – in much the similar ‘cautionary’ approach of a more ‘nondescript’ mentioning as one encounters for a male deific of some pertinence here also.

The fact that we have Leto / the Lycian deific that underlies Her acting in such demonstrable protection and upholding as to the sanctity of sacred space in those various inscriptions considered by Bryce should *seem* prima facie to allow us to infer that just the same thing is happening here.

What does that entail? Assumedly, a fairly direct linkage viz. Ḥšatrapati. But what kind? That is the question.

On the face of it, the idea of Ḥšatrapati *as* the ‘translation’ for the ‘Ruler / Protector of the Sacred Enclosure’ (viz. Lycian ‘qlahi ebijehi’) both makes obvious, logical sense … and yet runs into one rather obvious obstacle – the fact that the title in question is one oriented toward ‘Pati’. Which, as in Sanskrit, in Persianate languages is a “lord”, a “master” … “husband” (c.f. Greek ‘Potis’, as in ‘Despotis’, as in ‘Despot’; or, for that matter, Old Norse – ‘Freyr’).

Or is it?

When I turned to contemplating this mat(t)er some days ago, I had a sudden ‘feeling’ that Sanskrit ‘Pati’ must be able to be used in a non-masculine … indeed overtly *feminine* sense. That is – not as the ‘female counterpart’, ‘Patni’ (i.e. ‘Wife’ – c.f. the ‘Poina’ of ‘Despoina’ in Ancient Greek), but rather as an actual term utilized by a woman exercising what one might otherwise assume to be the archaic stationing of a powerful man. And, as it should turn out – my instinct was proven correct. Nyāyaratnasiṃha directed my attention to the work of the Sanskrit grammarian Pāṇini – whose Aṣṭādhyāyī (IV 1 33) confirms that just such an arrangement is, indeed, legitimate. In Sanskrit, at least, a ‘Kshetra Pati’ *could* indeed be a female figure, it should seem. I am unsure that there is any direct support for this notion in the older Persian languages, however – but it is still a rather intriguing point worth noting for comparative use elsewhere, perhaps.

The *other* possibility that we had countenanced is, in fact, advanced to us by Schwartz – to quote him upon the subject, “Now to Apollo himself. The Aram. juxtaposition ˀrtmwš ḥštrpty provides the names of the sibling pair called in Greek “the progeny of Leto,” and we may now see ḥštrpty (= Apollo), and not *ḥštrptyš = xšaθrapatiš (nominative), as reflecting a grammatical linkage in the Old Iranian phrasing which lies behind the Aramaic: xšaθrapatī , instrumental case, “(together) with Khshathrapati.””

Why is that particularly pertinent? Well, the instrumental case is a most wondrous thing. As one might presume – it renders the term in question one of an ‘instrument’, an ‘implement’, a vector or an operationalizer, a mechanism via which something is to be done (and perhaps ironically, in that last clause of mine, it’s the ‘something’ rather than the ‘mechanism’ which would be taking the instrumental case there).

Now, in Hindu terms – this is fairly exactly as we are accustomed to anticipate. When things go seriously sideways – we tend to find a particular deific called upon to act as the fairly *active* (re-)immanentization of Cosmic Law’s inviolate integral dominion. Rudra / Bhairava being the Deific Who I have most overtly in mind – called forth by the Gods for the express purpose of protecting and upholding Rta (Herself) via axe-wielding, arrow-shooting Fury. This is (partially) why He is hailed so as Vastospati – the Lord / Protector of the Vāstu. That is to say – of the ‘House’ or the ‘Ritual Space’ (c.f. SBr I 7 3 1, etc.); with Sayana’s commentary upon SBr V 2 4 13 noting that the ambit as to Vāstu incorporates both the grounds where sacral rites are to be conducted (yajna – bhumi), as well as the Smashana (Cremation Grounds), ‘etc.’ (‘Ādir’; and thank you, once again, to Nyāyaratnasiṃha for his assistance viz. ‘yajñabhūmiśmaśānādirvāstuḥ’).

This latter point may prove pertinent, perhaps, given the supposition that a ‘sepulchral’ connotation had been intended viz. ‘Khshathrapati’ – which is part of Schwartz’ efforts at linking the inscription to the Mesopotamian figure of Nergal, as noted above (his inference being that it is the Mesopotamian notion as to the ‘City of the Dead’ which is connoted via the hailing) … although leaving that dimension aside (the Mesopotamian one, not the (Indo-European) Realm of the Dead and correlate liminal space as potential (mesocosmic) crossover (crossroads?) en route toward same), even outside the Khshathrapati element there has long been contemplation as to the seeming saliency of ‘Pñtreñni’ and its relevant ambit viz. ”qlahi ebijehi” in specifically … cryptic terms. Bryce, for instance, notes the occurrence of the exact phrase – “ẽni:qlahi:ebiyehi:pñtreñni” [i.e. Mother (‘ẽni’) of This (‘ebiyehi’) Court / Sanctuary / Precinct (‘qlahi’) – Pñtreñni] not only within the Trilingual Inscription of Letoon … but *also* in multiple Lycian tomb warding textual emplacements (even across multiple cities).

The more truncated “ẽni qlahi ebiyehi” (i.e. minus the ‘pñtreñni’) is even more broadly attested within such context – and, in at least one case, is directly hailed as ‘Ẽni Mahanahi’ (i.e. ‘Mother of the Gods’). And to that point we would, once again, raise our comment viz. Aditi as Queen of the Pitrs [‘Forefathers’ – the Shades of the Ancestral Dead] per SBr VIII 4 3 7, etc. Inter, of course, various alia. We should be entirely unsurprised were further depth-research to turn up correlation for Hekate in such a schema – She is, after all, of seemingly Anatolian saliency; and there is, likewise, that Hittite ‘Underworld Sun’ Goddess to be considered also … at some other time.

Yet our point in once more raising the “ẽni:qlahi:ebiyehi:pñtreñni” suite of conceptry [and note: Bryce has a slightly different anglicization to the ‘ebijehi’ in use for transcription elsewhere] is actually quite a simple one. And approaches our Khshathrapati as if at right angles. Twice over, in fact.

These Lycian sepulchral warding inscriptions – they tend to set out in somewhat formulaic tones not only the perhaps expected dire and baleful threatening declarations [Bryce quotes a slightly differing exemplar – Lycian: “me ne qasttu:ẽni:qlahi:ebiyehi:se wedri: wehñtezi”, which he accordantly translates as “Let the Mother of this Precinct / Sanctuary (?) and the municipality(?) at Wehñta / Antiphellos judge him (i.e. the tomb violator”. He also notes that there is a Greek semi-translation accompanying the inscription – which is “rather more terse”, as he puts it; and which “seems to threaten the violator in much more forceful terms than does the Lycian”. The translation as to *that* ? “Leto will destroy him”.] … but *also*, alongside these, the ‘penalty rates’ for setting things back right where a transgression has occurred against the applicable propriety.

As it should happen, This Goddess is not the only Divinity called upon in various such contexts to undertake such Dread Sanction. The Lycian ‘Maliya’ is also frequently mentioned (on one of three occurrences for Her upon the Xanthos stele, Bryce notes, even alongside Artemis : “se mal[ i]yahi:se[ y ] ertemehi” – “of Maliya and Artemis”), with this Goddess being ‘interpretatio’ identified with Athena – and more specifically, Athena Polias; the former (broader) identification upon the basis of artefact evidence (including, intriguingly, an apparent Lycian presentation of the Judgement of Paris from the Iliad – featuring Athena, Aphrodite, and Paris with Lycian name-tagging alongside the representations), the latter being the contention of one J.D. Hawkins – who reasoned that the Lycian ‘Maliya Wedrẽñni’ (the latter being a recurrent epithet of Maliya) worked out effectively equivalent to the aforementioned ‘Athena of the City’ [‘Polias’].

However, upon that latter score we would not *quite* agree. As noted by Laroche, ‘Wedri-‘ isn’t used to translate ‘Polis’ ( πόλις ) in our much-aforementioned Trilingual Stele. Instead, the word utilized appears to be ‘teteri’ – which, perhaps unsurprisingly, means ‘city’. ‘Wedri-‘ and associated terms, meanwhile, instead appear to connote the ‘region’ [c.f. Bryce again, who makes exactly this inference] – with Carruba making the innovatively intriguing supposition that the actual term itself had archaically meant something like ‘[this] River Valley’ [and c.f. Yakubovich’s drawing from Puhvel to contemplate a broader Anatolian correlation here, viz. Hittite ‘udnē’ (‘land’) in relation to ‘watar’ (er. .. ‘water’), etc. – a situation assumedly “restricted to the mountainous areas, where river-valleys separated from each other by mountain ridges would be perceived as separate “countries”.”].

What this means is that ‘Maliya Wedrẽñni’ cannot readily be rendered *literally* as a Goddess ‘of the Polis’, of the *city itself* … although we may much more readily countenance the notion of the ‘Wedrẽñni’ in fact entailing not only the city, itself, but also its surrounding ‘territory’. Why is this pertinent for us? Well, you recall my earlier comments viz. ‘Kshetra-Pati’ ?

Now, of course, we should probably acknowledge the slight dysjunction between Sanskrit Kshetra and the Persianate ‘Kshatra’ (more properly ‘Xšathra’, these days, I suppose) … insofar as whilst both *do* refer to expanses of territory, they’re actually of somewhat differing origination. Insofar as the Sanskrit ‘Kshetra’ (not to be confused with Sanskrit ‘Kshatra’ ( क्षत्र ) ) is more focused upon the ‘land’ or ‘place’ dimension, whilst the Persianate is oriented around the ‘Rulership’ thereof (hence why it has a cognate in Sanskrit ‘Kshatra’ (whence ‘Kshatriya’) – not to be confused with Sanskrit ‘Kshetra’ ( क्षेत्र ) ). This is partially why, as it happens, that Mayrhofer instead chose to approach the mysterious ‘Khshathrapati’ of the trilingual inscription as meaning ‘Lord of Power’ (‘Herr der Herrschermacht’) – and pointing toward the occurrence at Yasna 44 9 for a hailing [implicitly in the direction of Ahura Mazda] of ‘paⁱti- […] xšaθrahyā’. Molina-Valero posits that the sense intended was one of “a kind of divinisation of power”. Yet we are also cognizant of Moulton’s rendering as to the relevant Gathic phrase as “the Lord of the Dominion”, whilst Mills goes for “Kingdom’s Lord”.

As applies Kshetra – it is quite the ‘scalable’ term, with an ambit that can run in scope all the way from the comparatively constrained ‘Ritual Enclosure’ or ‘Temple’ (Temple Precinct … ? – c.f. Ancient Greek ‘Temenos’ / ‘τέμενος’), up through a ‘Field’ or a ‘Meadow’, and on into ‘Realm’, ‘Dominion’, or ‘Country’ sized conceptry … and even further (if the fruits of my this morning’s around-Dawn harrassing of Nyāyaratnasiṃha as to the ambit of the ‘Kshetra-Patni’ of AV-S II 12 1 was correct) all the way up to entire ‘Plane’ / ‘Loka’ (‘Tri-Loka’, in fact – and incipiently, therefore, a Tri-Devi … perhaps rather like a certain Anatolian Goddess in that regard) and therefore rather ‘cosmological’ scale.

For our purposes, we might (*exceptionally* briefly!) mention but two of the ‘styles’ of Roudran hailing that are built around this concept – not because I am attempting to out-do Schwartz at his own game(s) viz. the ‘exotic origins’