As hype builds up for Christopher Nolan’s Odysseus exercise, I can see that quite a range and array of ‘Accepted Pop-Cultural Kernels’ around the Homeric and Bronze Age milieu are going to shamble forth into our ken of vision like ever so many skeleton warriors.

In some of these areas, interesting and positive progress has indeed been made over the years – to the point that when the preview image featuring Matt Damon in a … Hollywood-pastiche of Classical armouring (i.e. basically what ‘Everybody Expects’ for a Homeric protagonist – a sort of ‘more archaic looking Roman’, replete with an open-faced helm and longitudinal ‘broom’ crest, etc.), it is not only the Classical academics and other such voices in the far-flung and underfunded wildernesses who express critique.

Yet some of these shibboleths – no matter how solidly they are, repeatedly, dealt to … just simply refuse to ‘stay down’, and continue to be endlessly repeated by people who have become interested in the general subject and are marvelling at the seeming-manifestation for the ‘familiar-but-alien’ Ancient World allegedly conveyed via the conceit in question.

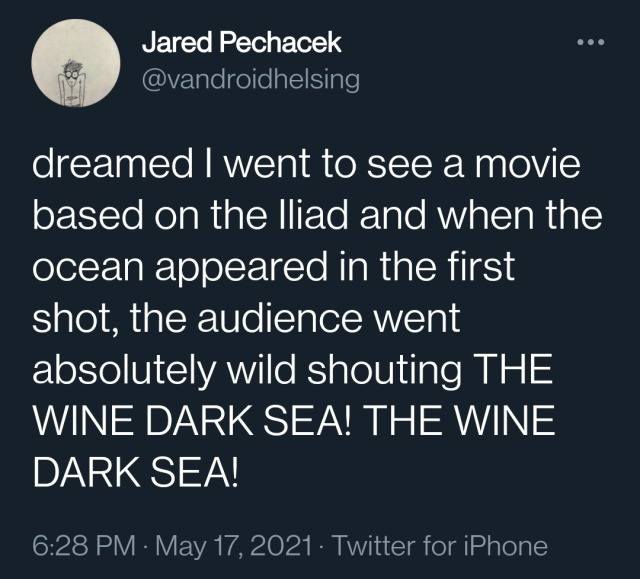

Earlier today, I had happened to run into a post from a page whose output I usually have some time and respect for, featuring a meme concerning that most evocative of Homeric phrasings – the “wine-dark sea”.

And, accordingly, the comment section beneath said meme, in which a number of people excitedly mentioned or postulated upon the (inevitably) accompanying prospect for the more archaic Greek to have, reputedly, not been able to see Blue (etc.), and therefore why one does not find such a straightforwardly simple thing as “The Blue Sea” as the relevant repeated construction.

Now I thought I had already written something at length upon this, but I can’t seem to find it. So here’s a somewhat brief suite of points I’d dredged up from one of my own bemused reactions to all of this, upon a previous occasion some years ago, in the mean-time.

If you want to ‘skip to the end’ … the short version is that contrary to what you might have read, the Ancient Greeks did have word(s) for Blue, which were utilized for ‘Blue’ (well, blue-coloured), and with these being attested right back into the Mycenaean era.

So no, no the “wine-dark sea” thing isn’t because they didn’t have such a concept nor colouration. But we’ll get to that in a bit.

As applies why Homer doesn’t go for a ‘blue sea’ …

First –

A more simple explanation is that it’s poetry … written by a man who was supposed to be blind (at least, per various traditions upon the subject).

The latter dimension would certainly prove a rather more fundamental obstacle to ‘seeing blue’ than purported ‘civilizational colour-blindness’ … and yet I would instead suggest it to be the former feature which is of greater (and demonstrable) pertinence herein.

Many of the colour references in Homer are very much poetic phrasings – instead of simply coming out and saying something is such-and-such a colour (which, assumedly, the Greeks of his day and Bronze Age antiquity could see).

We would not tend to think that they lacked knowledge of a given colour simply because they used indirect ways of communicating it in epic poetry.

And we would also do well to observe that translations are rather limited precisely via that fact – and that the essential underlying sense to what might be taken ‘merely’ as a colour-term, can in fact be rather more ‘animate’, so to speak, than a mere listing of hue.

So, as applies the ‘Glaukopis’ ( γλαυκῶπις ) utilized for Athena’s Eyes – one often encounters ‘Flashing-‘ or ‘Shining-‘ as the description, rather than the ‘Blue-Grey’ (or ‘Blue-Green’, ‘Grey-‘, etc.) which would be interpreted were one merely to render ‘Glaukos’ more directly. (And, speaking of ‘Eye’ elements – whilst it’s not Homeric, I had been reminded also for the situation of Nemesis’ Eyes being described as χαροπὰ within Mesomedes’ Hymn to Her : Maxwell-Stuart having this as ‘Amber’, whilst also observing that ‘Fieriness of Eye’ could mean, per Adamantius, ‘bloodshot eyes’, and with a potential ambit of meaning very much in keeping with the Hindu utilization for the same human descriptive element when the Devi Rages)

Similarly, one encounters mentions for the great Greek heroes – Diomedes & Achilles being whom I’m thinking of in particular – when empowered to superhuman greatness, as being, effectively, ‘aflame’, and with panoply thusly to match (see, for instance, “πῦρ” at V 4, for Diomedes – like ‘pyro’).

And one could certainly, if perhaps somewhat euhemerically, suggest that very shiny bronze and a fine red helmet crest, might account for the fact that the helm(s) in question are supposed to be of such a hailing – although at this point I would note that in the Vedic correlate for the same archaic Indo-European understanding [viz. the RV / AV-S hymnals oriented around ‘Manyu’ – ref. ‘Minerva’, the ‘Menos’ imparted by Athena, etc.], the ‘fiery’ terminology is not only also encountered, but is of a metaphysical meaning connected to the divine energy to have been invested into the warrior (and army) in question. Which is, of course, exactly the manner in which these illustrative descriptions are deployed within the context of the Iliad [Books V & XIX for Diomedes & Achilles, in particular, respectively].

In other words – expecting those ‘flame’ descriptions of the panoply of a great (indeed, divinely empowered) warrior to merely be because something is ‘shiny orange’ … is fundamentally missing the point. Even if you don’t want to get into the archaic Indo-European ritual-religious dimension being referenced through that Homeric illustration, you can readily come up with some pretty foundational rationales for why the ‘fiery’ descriptors – fierce, destructive, furious and roiling, unstoppable, etc. etc. – are there which go quite beyond the ‘orange and shiny’.

So, as applies this ‘wine-dark sea’ business … one interpretation might follow Heyschius, whose lexicon had parsed ‘οἰνωπόν’ (oinopon – ‘wine-looking’ / ‘like wine’) as “πορφύρεον” or “μέλανα”. The second term would, assumedly, have something to do with why it’s a “wine-dark” sea we keep hearing about, but it’s the former which is of greater pertinence here.

Beekes (a linguist with whom I have … a rather substantial reserve of frustration, most of the time – so it’s nice to have seen him doing something useful), has πορφύρεος in his etymological dictionary of Greek as “‘boiling, whirly’, of the sea (Hom., Alc.)”, and effectively having wound up an overlapping (indeed, homophonic) term with the ‘purple’ one (“πορφύρα” for the colour, “πορφύρω” for the action).

I would suggest that if one looks at wine which has freshly been poured – other than the prospect for it, perhaps, being of a reddish-purple colour (or a lighter golden one) .. the thing that one is going to be noticing is the ‘bubbles’ and ‘froth’ which are at the surface.

Rather like, you might suspect … the foam etc. which one readily observes upon the sea – particularly when it’s choppy, and the white crests of waves begin to appear.

In other words – the ‘wine-dark sea’ … rather the ‘wine-looking sea’ , is not idly ‘blue’ : but is ever in motion, and with tangible physical expressions thereof in the ‘bubbly’ etc. expressions of this upon its surface.

How very naturalistic.

And much more useful than simply saying “blue” – which would, even in colouration terms, likely be at best an incomplete descriptor.

But let’s get back to that colour, now, itself.

It is also the case that the Ancient Greeks had a word for ‘Blue’ (well, Blue-Black, perhaps, is closer to the mark – a similar situation shows up viz. ‘Nila’ (नील) in Sanskrit (one also can use Kāla to mean ‘Blue-Black’, likewise), and also ‘blár’ i Old Norse (we have often phrased it ‘Corpse-Black’ or ‘Bruise-Black’) ).

That word is, of course, κύανος – which, oddly enough, does show up in Homer.

It is also where we get modern English ‘Cyan’ from – although the term has shifted a bit in meaning to become more of a blue-green, than a ‘blue’.

Now, we can tell that this is the correct understanding [i.e. ‘(Dark)-Blue’] based around a few things. And I shall spare the reader some delvings into slightly theoretical comparative Indo-European conceptry (it’s around, inter alia, the idea for Poseidon’s κυανοχαῖτα [ref. Orphic Hymn XVI / XVII 1 (depending upon which iteration one is using, either hymn sixteen or seventeen, line one)] , as a blue-curly-hair description being rather apt for … the sea, with its blue and curl-motion characteristic appearance ; but also run cross-correlate with some interesting Hindu conceptry and some further Ancient Greek liturgical hailings around the roiling (dark-)blue of the Sky), and just go directly for something one can hang one’s proverbial hat more straightforwardly upon.

Smith, Wayte, & Marindin [admittedly, writing in the late 1800s] had the following to say:

“Many writers have supposed that the word κύανος in Homer stands for steel; but it has been proved by Lepsius that this is incorrect, and that it really means either lapis-lazuli or an artificial imitation of that mineral, and the view of Lepsius has been confirmed by the discovery of a frieze of alabaster and glass (θριγκὸς κυάνολο) in one of the rooms of the very early palace at Tiryns (Schliemann, Tiryns, p. 287).”

[‘Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities’, ‘Metallium’ / μέταλλον entry; 1890]

Beekes, working over a century later, had this within that aforesaid etymological dictionary of Greek (prepared for Lubotsky’s / Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series):

“κύανος [m.] name of a dark blue substance, ‘enamel, lapis lazuli, bronze copper carbonate’ (Il.); […]

- DIAL Myc. ku-wa-no ‘smalt’, also ku-wa-no-wo-ko /kuano-worgos/ ‘smalt-worker’.

- COMP Often as a first member, e.g. κυανό-πρῳρος ‘with a dark blue prow’ (Hom., B.),

[…]

DER κυάνεος (ῡ metrically lengthened) made of κ., usually dark-blue (Il.); on the mg. Capelle RhM 101 (1958): 10 and 35 - ETYM. Perhaps a loan from Hitt. kuu̯anna(n)- ‘(blue as) copper, ornamental stone’ (Friedrich 1952 s.v.).”

As applies the Hittite linkage, Danka & Witczak (with “kuwannaš” for the relevant Hittite term) observe the prospect for a PIE root – *k̂wn̥Hos , with both glass-making and metallurgical applications for the term’s descendants being logically correlated; and with ‘blue-ish’ usages also cited for such archaic Homeric awareness into the bargain.

Frankly, at this rate, what ought interest people more is not marvelling at this mysterious non-fact of “Bronze Age / Homeric Greeks Couldn’t See Blue” (they clearly could) – but instead at how a canard from the 1800s has continued to massively distort the situation so many people somehow manage to not see the truth of the matter, even when the literal word for blue gets used in Homer in the first place.

But, of course, it’s far less ‘exotic’ if there’s such an otherizeable ‘distinction’ to the past – so it shall continue merrily regardless.

And an endless tide of “DID YOU KNOW” clickbaitery (even from a century and more afore the invention of the computer mouse) shall form quite the ‘wine-dark sea’ for people to both sail and become inebriated upon.

And that’s before we see what ‘fresh’ bemusements a further big-budget Hollywood production adds to proceedings later this year !